Bundles and Packages

In this season of giving, let’s stop to consider one of the greatest gifts given to us by modern computer systems: the gift of abstraction.

Consider those billions of people around the world who use computers and mobile devices on a daily basis. They do this without having to know anything about the millions of CPU transistors and SSD sectors and LCD pixels that come together to make that happen. All of this is thanks to abstractions like files and directories and apps and documents.

This week on NSHipster, we’ll be talking about two important abstractions on Apple platforms: bundles and packages. 🎁

Despite being distinct concepts, the terms “bundle” and “package” are frequently used interchangeably. Part of this is undoubtedly due to their similar names, but perhaps the main source of confusion is that many bundles just so happen to be packages (and vice versa).

So before we go any further, let’s define our terminology:

-

A bundle is a directory with a known structure that contains executable code and the resources that code uses.

-

A package is a directory that looks like a file when viewed in Finder.

The following diagram illustrates the relationship between bundles and packages, as well as things like apps, frameworks, plugins, and documents that fall into either or both categories:

Bundles

Bundles are primarily for improving developer experience by providing structure for organizing code and resources. This structure not only allows for predictable loading of code and resources but allows for system-wide features like localization.

Bundles fall into one of the following three categories, each with their own particular structure and requirements:

-

App Bundles, which contain an executable that can be launched,

an

Info.plistfile describing the executable, app icons, launch images, and other assets and resources used by the executable, including interface files, strings files, and data files. - Framework Bundles, which contain code and resources used by the dynamic shared library.

- Loadable Bundles like plug-ins, which contain executable code and resources that extend the functionality of an app.

Accessing Bundle Contents

In apps, playgrounds, and most other contexts

the bundle you’re interested in is accessible through

the type property Bundle.main.

And most of the time,

you’ll use url(for

(or one of its variants)

to get the location of a particular resource.

For example,

if your app bundle includes a file named Photo.jpg,

you can get a URL to access it like so:

Bundle.main.url(forFor everything else,

Bundle provides several instance methods and properties

that give the location of standard bundle items,

with variants returning either a URL or a String paths:

| URL | Path | Description |

|---|---|---|

executable |

executable |

The executable |

url(for |

path(for |

The auxiliary executables |

resource |

resource |

The subdirectory containing resources |

shared |

shared |

The subdirectory containing shared frameworks |

private |

private |

The subdirectory containing private frameworks |

built |

built |

The subdirectory containing plug-ins |

shared |

shared |

The subdirectory containing shared support files |

app |

The App Store receipt |

Getting App Information

All app bundles are required to have an Info.plist file

that contains information about the app.

Some metadata is accessible directly through instance properties on bundles,

including bundle and bundle.

import Foundation

let bundle = Bundle.main

bundle.bundleYou can get any other information

by subscript access to the info property.

(Or if that information is presented to the user,

use the localized property instead).

bundle.infoGetting Localized Strings

One of the most important features that bundles facilitate is localization. By enforcing a convention for where localized assets are located, the system can abstract the logic for determining which version of a file to load away from the developer.

For example,

bundles are responsible for loading the localized strings used by your app.

You can access them using the localized method.

import Foundation

let bundle = Bundle.main

bundle.localizedHowever, it’s almost always a better idea to use

NSLocalized so that utilities like genstrings

can automatically extract keys and comments to .strings files for translation.

NSLocalized$ find . \( -name "*.swift" ! \ # find all Swift files

! -path "./Carthage/*" \ # ignoring dependencies

! -path "./Pods/*" \ # from Carthage and CocoaPackages

Packages are primarily for improving user experience by encapsulating and consolidating related resources into a single unit.

A directory is considered to be a package by the Finder if any of the following criteria are met:

- The directory has a special extension like

.app,.playground, or.plugin - The directory has an extension that an app has registered as a document type

- The directory has an extended attribute designating it as a package *

Accessing the Contents of a Package

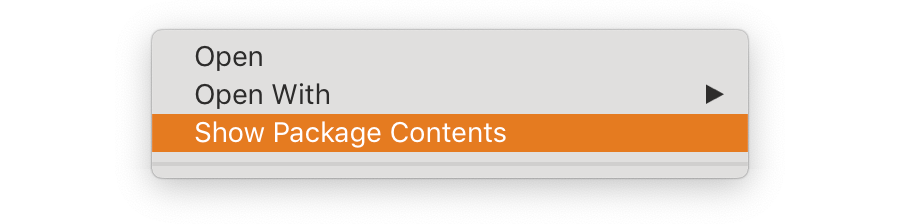

In Finder, you can control-click to show a contextual menu with actions to perform on a selected item. If an item is a package, “Show Package Contents” will appear at the top, under “Open”.

Selecting this menu item will open a new Finder window from the package directory.

You can, of course, access the contents of a package programmatically, too. The best option depends on the kind of package:

- If a package has bundle structure,

it’s usually easiest to use

Bundleas described in the previous section. - If a package is a document, you can use

NSDocumenton macOS andUIDocumenton iOS. - Otherwise, you can use

Fileto navigate directories, files, and symbolic links, andWrapper Fileto read and write to file descriptors.Handler

Determining if a Directory is a Package

Although it’s up to the Finder how it wants to represent files and directories, most of that is delegated to the operating system and the services responsible for managing Uniform Type Identifiers (UTIs).

To determine whether a file extension

is one of the built-in system package types

or used by an installed app as a registered document type,

access the URL resource is:

let url: URL = …

let directoryOr, if you don’t have a URL handy

and wanted to check a particular filename extension,

you could instead use the Core Services framework to make this determination:

import Foundation

import CoreAs we’ve seen, it’s not just end-users that benefit from abstractions — whether it’s the safety and expressiveness of a high-level programming language like Swift or the convenience of APIs like Foundation, we as developers leverage abstraction to make great software.

For all that we may (rightfully) complain about abstractions that are leaky or inverted, it’s important to take a step back and realize how many useful abstractions we deal with every day, and how much they allow us to do.