Dictionary Services

This week’s article is about dictionaries.

No, not the Dictionary / NSDictionary / CFDictionary

we encounter every day,

but rather those distant lexicographic vestiges of school days past.

Though widely usurped of their ‘go-to reference’ status by the Internet, dictionaries and word lists serve an important role behind the scenes for features ranging from spell check, grammar check, and auto-correct to auto-summarization and semantic analysis. So, for your reference, here’s a look at the ways and means by which computers give meaning to the world through words, in Unix, macOS, and iOS.

Unix

Nearly all Unix distributions include

a small collection newline-delimited list of words.

On macOS, these can be found at /usr/share/dict:

$ ls /usr/share/dict

README

connectives

propernames

web2

web2a

words@ -> web2

Symlinked to words is the web2 word list,

which —

though not exhaustive —

is still a sizable corpus:

$ wc /usr/share/dict/words

235886 235886 2493109

Skimming with head shows what fun lies herein.

Such excitement is rarely so palpable as it is among words beginning with “a”:

$ head /usr/share/dict/words

A

a

aa

aal

aalii

aam

Aani

aardvark

aardwolf

Aaron

These giant, system-provided text files make it easy to

grep crossword puzzle clues,

generate mnemonic passphrases, and

seed databases.

But from a user perspective,

/usr/share/dict’s monolingualism

and lack of associated meaning

make it less than helpful for everyday use.

macOS builds upon this with its own system dictionaries. Never one to disappoint, the operating system’s penchant for extending Unix functionality by way of strategically placed bundles and plist files is in full force here with how dictionaries are distributed.

macOS

The macOS analog to /usr/share/dict can be found in /Library/Dictionaries.

A quick peek into the shared system dictionaries

demonstrates one immediate improvement over Unix:

acknowledging the existence of languages other than English:

$ ls /Library/Dictionaries/

Apple Dictionary.dictionary/

Diccionario General de la Lengua Española Vox.dictionary/

Duden Dictionary Data Set I.dictionary/

Dutch.dictionary/

Italian.dictionary/

Korean - English.dictionary/

Korean.dictionary/

Multidictionnaire de la langue française.dictionary/

New Oxford American Dictionary.dictionary/

Oxford American Writer's Thesaurus.dictionary/

Oxford Dictionary of English.dictionary/

Oxford Thesaurus of English.dictionary/

Sanseido Super Daijirin.dictionary/

Sanseido The WISDOM English-Japanese Japanese-English Dictionary.dictionary/

Simplified Chinese - English.dictionary/

The Standard Dictionary of Contemporary Chinese.dictionary/

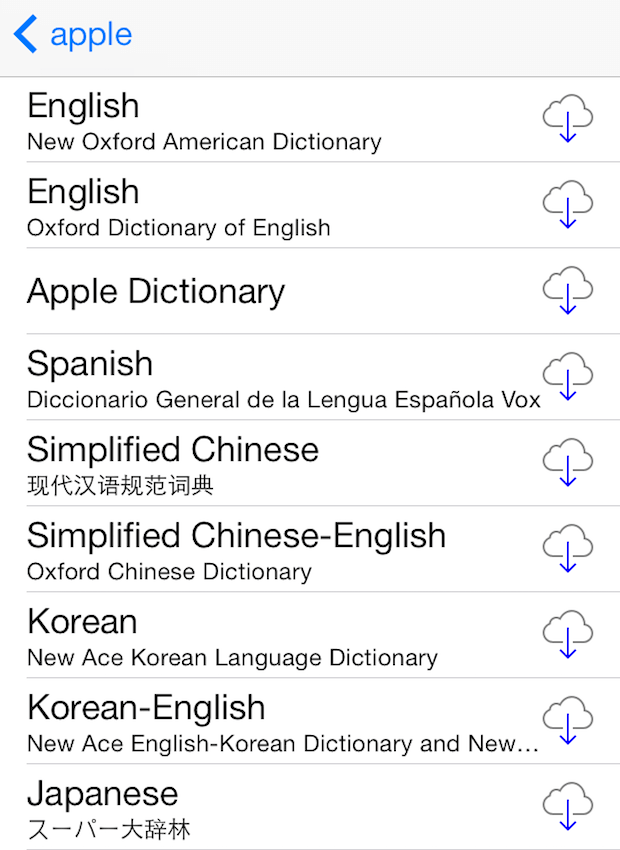

macOS ships with dictionaries in Chinese, English, French, Dutch, Italian, Japanese, and Korean, as well as an English thesaurus and a special dictionary for Apple-specific terminology.

Diving deeper into the rabbit hole,

we peruse the .dictionary bundles to see them for what they really are:

$ ls "/Library/Dictionaries/New Oxford American Dictionary.dictionary/Contents"

Body.data

DefaultA filesystem autopsy reveals some interesting implementation details. For New Oxford American Dictionary, in particular, its contents include:

- Binary-encoded

Key,Text.data Key, andText.index Content.data - CSS for styling entries

- 1207 images, from A-Frame to Zither.

- Preference to switch between US English Diacritical Pronunciation and International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA)

Proprietary binary encoding like this would usually be the end of the road in terms of what one could reasonably do with data. Luckily, Core Services provides APIs to read this information.

Getting the Definition of Words

To get the definition of a word on macOS,

one can use the DCSCopy function

found in the Core Services framework:

import Foundation

import Core#import <CoreWait, where did all of those great dictionaries go?

Well, they all disappeared into that first NULL argument.

One might expect to provide a DCSCopy type here —

as prescribed by the function definition.

However, there are no public functions to construct or copy such a type,

making nil the only available option.

The documentation is as clear as it is stern:

This parameter is reserved for future use, so pass

NULL. Dictionary Services searches in all active dictionaries.

“Dictionary Services searches in all active dictionaries”, you say? Sounds like a loophole!

Setting Active Dictionaries

Now, there’s nothing programmers love to hate to love more than exploiting loopholes to side-step Apple platform restrictions. Behold: an entirely error-prone approach to getting, say, thesaurus results instead of the first definition available in the standard dictionary:

NSUser“But this is macOS, a platform whose manifest destiny cannot be contained by meager sandboxing attempts from Cupertino!”, you cry. “Isn’t there a more civilized approach? Like, say, private APIs?”

Why yes. Yes there are.

Exploring Private APIs

Not publicly exposed but still available through Core Services are a number of functions that cut closer to the dictionary services functionality we crave:

extern CFArrayPrivate as they are, these functions aren’t about to start documenting themselves. So let’s take a look at how they’re used:

Getting Available Dictionaries

NSMapGetting Definition for Word

With instances of the elusive DCSDictionary type available at our disposal,

we can now see what all of the fuss is about with

that first argument in DCSCopy:

NSString *word = @"apple";

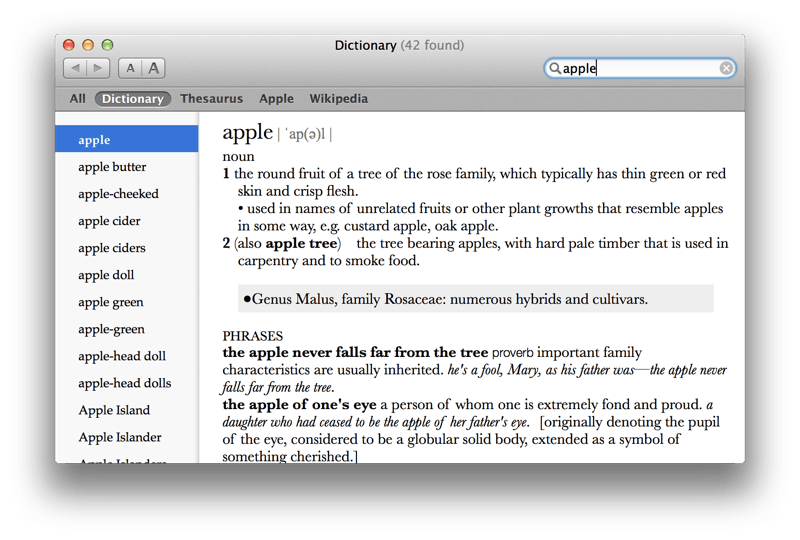

for (NSString *name in availableMost surprising from this experimentation is the ability to access the raw HTML for entries, which — combined with a dictionary’s bundled CSS — produces the result seen in Dictionary.app.

iOS

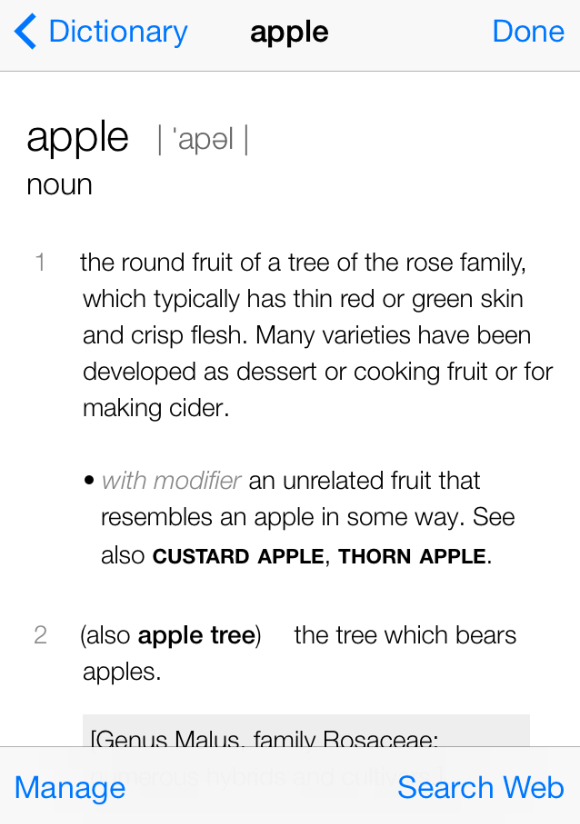

iOS development is a decidedly more by-the-books affair,

so attempting to reverse-engineer the platform

would be little more than an academic exercise.

Fortunately, a good chunk of functionality is available

through an obscure UIKit class, UIReference.

UIReference is similar to an

MFMessage in that provides

a minimally-configurable view controller around system functionality

that’s intended to present modally.

You initialize it with the desired term:

UIReference

This is the same behavior that one might encounter when tapping the “Define” menu item on a highlighted word in a text view.

UIReference also provides

the class method dictionary.

A developer would do well to call this

before presenting a dictionary view controller

that will inevitably have nothing to display.

[UIReferenceFrom Unix word lists to their evolved .dictionary bundles on macOS

(and presumably iOS, too),

words are as essential to application programming

as mathematical constants and the

“Sosumi” alert noise.

Consider how the aforementioned APIs can be integrated into your own app,

or used to create a kind of app you hadn’t previously considered.