#pragma

#pragma declarations are a mark of craftsmanship in Objective-C.

Although originally used to make source code compatible across different compilers,

Xcode-savvy programmers use #pragma declarations to very different ends.

Whereas other preprocessor directives

allow you to define behavior when code is executed,

#pragma is unique in that it gives you control

at the time code is being written —

specifically,

by organizing code under named headings

and inhibiting warnings.

As we’ll see in this week’s article,

good developer habits start with #pragma mark.

Organizing Your Code

Code organization is a matter of hygiene. How you structure your code is a reflection of you and your work. A lack of convention and internal consistency indicates either carelessness or incompetence — and worse, it makes a project more challenging to maintain over time.

We here at NSHipster believe that

code should be clean enough to eat off of.

That’s why we use #pragma mark to divide code into logical sections.

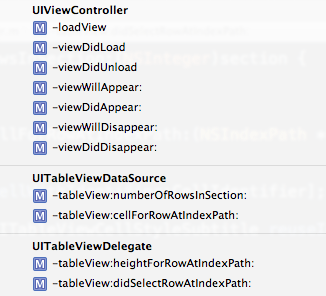

If your class overrides any inherited methods,

organize them under common headings according to their superclass.

This has the added benefit of

describing the responsibilities of each ancestor in the class hierarchy.

An NSInput subclass, for instance,

might have a group marked NSInput,

followed by NSStream,

and then finally NSObject.

If your class adopts any protocols,

it makes sense to group each of their respective methods

using a #pragma mark header with the name of that protocol

(bonus points for following the same order as the original declarations).

Finding it difficult to make sense of your app’s MVC architecture?

(“Massive View Controller”, that is.)

#pragma marks allow you to divide-and-conquer!

With a little practice,

you’ll be able to identify and organize around common concerns with ease.

Some headings that tend to come up regularly include

initializers,

helper methods,

@dynamic properties,

Interface Builder outlets or actions,

and handlers for notification or

Key-Value Observing (KVO) selectors.

Putting all of these techniques together,

the @implementation for

a View class that inherits from UITable

might organize Interface Builder actions together at the top,

followed by overridden view controller life-cycle methods,

and then methods for each adopted protocol,

each under their respective heading.

@implementation ViewNot only do these sections make for easier reading in the code itself, but they also create visual cues to the Xcode source navigator and minimap.

Inhibiting Warnings

Do you know what’s even more annoying than poorly-formatted code? Code that generates warnings — especially 3rd-party code. Is there anything more irksome than a vendor SDK that generates dozens of warnings each time you hit ⌘R? Heck, even a single warning is one too many for many developers.

Warnings are almost always warranted,

but sometimes they’re unavoidable.

In those rare circumstances where you are absolutely certain that

a particular warning from the compiler or static analyzer is errant,

#pragma comes to the rescue.

Let’s say you’ve deprecated a class:

@interface DeprecatedNow,

deprecation is something to be celebrated.

It’s a way to responsibly communicate future intent to API consumers

in a way that provides enough time for them to

migrate to an alternative solution.

But you might not feel so appreciated if you have

CLANG_WARN_DEPRECATED_OBJC_IMPLEMENTATIONS enabled in your project.

Rather than being praised for your consideration,

you’d be admonished for implementing a deprecated class

.

One way to silence the compiler would be to

disable the warnings by setting -Wno-deprecated-implementations.

However,

doing this for the entire project would be too coarse an adjustment,

and doing this for this file only would be too much work.

A better option would be to use #pragma

to inhibit the unhelpful warning

around the problematic code.

Using #pragma clang diagnostic push/pop,

you can tell the compiler to ignore certain warnings

for a particular section of code:

#pragma clang diagnostic push

#pragma clang diagnostic ignored "-Wdeprecated-implementations"

@implementation DeprecatedBefore you start copy-pasting this across your project

in a rush to zero out your warnings,

remember that,

in the overwhelming majority of cases,

Clang is going to be right.

Fixing an analyzer warning is strongly preferred to ignoring it,

so use #pragma clang diagnostic ignored as a method of last resort.

Though it skirts the line between comment and code,

#pragma remains a vital tool in the modern app developer’s toolbox.

Whether it’s for grouping methods or suppressing spurious warnings,

judicious use of #pragma can go a long way

to make projects easier to understand and maintain.

Like the thrift store 8-track player you turned into that lamp in the foyer,

#pragma remains a curious vestige of the past:

Once the secret language of compilers,

now re-purposed to better-communicate intent to other programmers.

How delightfully vintage!