Unmanaged

APIs do more than just exposing functionality to developers. They also communicate values about how the API should be used and why. This communication is what makes naming things one of the Hard Parts of computer science; it’s what separates the good APIs from the great.

A reading of Swift’s standard library shows a clear demarcation between the safety and reliability that Swift advertises on one side and the tools necessary for Objective-C interoperability on the other. Types with names like Int, String, and Array let you expect straightforward usage and unsurprising behavior, while it’s impossible to create an Unsafe or Unmanaged instance without thinking “here be dragons.”

Here we take a look at Unmanaged, a wrapper for unclearly-memory-managed objects and the hot-potatoesque way of properly handling them. But to start, let’s rewind the clock a bit.

Automatic Reference Counting

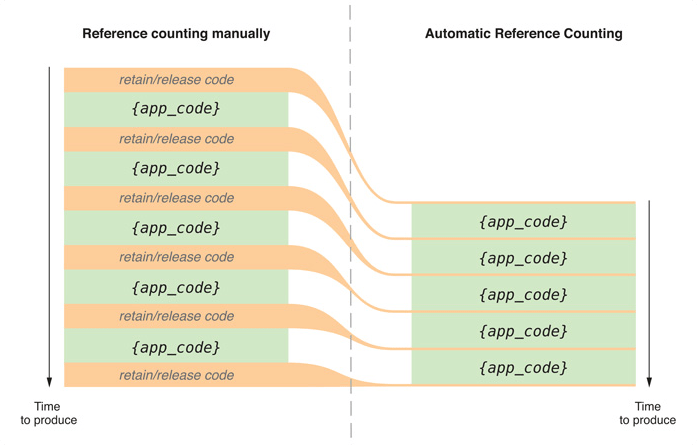

Back in the Stone Age (aka 2011), reference counting in Objective-C was still a manual affair. Each reference-retaining operation needed to be balanced with a corresponding release, lest an application’s memory take on an air of phantasmagoria, with zombies dangling and memory leaking… Gross. Carefully tending the reference count of one’s objects was a constant chore for developers and a major hurdle for newcomers to the platform.

The advent of automatic reference counting (ARC) made all of that manual memory management unnecessary. Under ARC, the compiler inserts the retain/release/autorelease calls for you, reducing the cognitive load of applying the rules at every turn. If this graphic doesn’t convince you of the boon of dropping manual memory management, nothing will:

Now, in this post-ARC world, all Objective-C and Core Foundation types returned from Objective-C methods are automatically memory managed, leaving Core Foundation types returned from C functions as the lone holdout. For this last category, management of an object’s ownership is still done with calls to CFRetain() and CFRelease() or by bridging to Objective-C objects with one of the __bridge functions.

To help understand whether or not a C function returns objects that are owned by the caller, Apple uses naming conventions defined by the Create Rule and the Get Rule:

-

The Create Rule states that a function with

CreateorCopyin its name returns ownerships to the call of the function. That is to say, the caller of aCreateorCopyfunction will eventually need to callCFReleaseon the returned object. -

The Get Rule isn’t so much a rule of its own as it is a catch-all for everything that doesn’t follow the Create Rule. A function doesn’t have

CreateorCopyin its name? It follows the Get rule instead, returning without transferring ownership. If you want the returned object to persist, in most cases it’s up to you to retain it.

If you’re a belt-and-suspenders-and-elastic-waistband programmer like I am, check the documentation as well. Even when they follow the proper name convention, most APIs also explicitly state which rule they follow, and any exceptions to the common cases.

Wait—this article is about Swift. Let’s get back on track.

Swift uses ARC exclusively, so there’s no room for a call to CFRelease or __bridge_retained. How does Swift reconcile this “management-by-convention” philosophy with its guarantees of memory safety?

This occurs in two different ways. For annotated APIs, Swift is able to make the conventions explicit—annotated CoreFoundation APIs are completely memory-managed and provide the same promise of memory safety as do bridged Objective-C or native Swift types. For unannotated APIs, however, Swift passes the job to you, the programmer, through the Unmanaged type.

Managing Unmanaged

While most CoreFoundation APIs have been annotated, some significant chunks have yet to receive attention. As of this writing, the Address Book framework seems the highest profile of the unannotated APIs, with several functions taking or returning Unmanaged-wrapped types.

An Unmanaged<T> instance wraps a CoreFoundation type T, preserving a reference to the underlying object as long as the Unmanaged instance itself is in scope. There are two ways to get a Swift-managed value out of an Unmanaged instance:

take: returns a Swift-managed reference to the wrapped instance, decrementing the reference count while doing so—use with the return value of a Create Rule function.Retained Value()

take: returns a Swift-managed reference to the wrapped instance without decrementing the reference count—use with the return value of a Get Rule function.Unretained Value()

In practice, you’re better off not even working with Unmanaged instances directly. Instead, take... the underlying instance immediately from the function’s return value and bind that.

Let’s take a look at this in practice. Suppose we wish to create an ABAddress and fetch the name of the user’s best friend:

let bestWith Swift 1.2’s improved optional bindings, it’s a piece of cake to unwrap, take the underlying value, and cast to a Swift type.

Better Off Without

Now that we’ve looked at how to work with Unmanaged, let’s look at how to get rid of it altogether. If Unmanaged references are returned from calls to your own C functions, you’re better off using annotations. Annotations let the compiler know how to automatically memory-manage your return value: instead of an Unmanaged<CFString>, you receive a CFString, which is type-safe and fully memory-managed by Swift.

For example, let’s take a function that combines two CFString instances and annotate that function to tell Swift how to memory-manage the resulting string. Following the naming conventions described above, our function will be called Create—that name communicates that the caller will own the returned string.

CFStringSure enough, in the implementation you can see that this creates result with CFString and returns it without a balancing CFRelease:

CFStringIn our Swift code, just as above, we still need to manage the memory manually. Our function is imported as returning an Unmanaged<CFString>!:

// imported declaration:

func CreateSince our function follows the naming conventions described in the Create Rule, we can turn on the compiler’s implicit bridging to eliminate the Unmanaged wrapper. Core Foundation provides two macros—namely, CF_IMPLICIT_BRIDGING_ENABLED and CF_IMPLICIT_BRIDGING_DISABLED—that turn on and off the Clang arc_cf_code_audited attribute:

CF_IMPLICIT_BRIDGING_ENABLED // get rid of Unmanaged

#pragma clang assume_nonnull begin // also get rid of !s

CFStringBecause Swift now handles the memory management for this return value, our code is simpler and skips use of Unmanaged altogether:

// imported declaration:

func CreateFinally, when your function naming doesn’t comply with the Create/Get Rules, there’s an obvious fix: rename your function to comply with the Create/Get Rules. Of course, in practice, that’s not always an easy fix, but having an API that communicates clearly and consistently pays dividends beyond just avoiding Unmanaged. If renaming isn’t an option, there are two other annotations to use: functions that pass ownership to the caller should use CF_RETURNS_RETAINED, while those that don’t should use CF_RETURNS_NOT_RETAINED. For instance, the poorly-named Make is shown here with manual annotations:

CF_RETURNS_RETAINED

__nonnull CFStringOne gets that feeling that Unmanaged is a stopgap measure—that is, a way to use CoreFoundation while the work of annotating the mammoth API is still in progress. As functions are revised to interoperate more cleanly, each successive Xcode release may allow you to strip take calls from your codebase. Yet until the sun sets on the last CFUnannotated, Unmanaged will be there to help you bridge the gap.