Contact Tracing

An ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure.

Early intervention is among the most effective strategies for treating illnesses. This is true not only for the human body, for society as a whole. That’s why public health officials use contact tracing as their first line of defense against the spread of infectious disease in a population.

We’re hearing a lot about contact tracing these days, but the technique has been used for decades. What’s changed is that thanks to the ubiquity of personal electronic devices, we can automate what was — up until now — a labor-intensive, manual process. Much like how “computer” used to be a job title held by humans, the role of “contact tracer” may soon be filled primarily by apps.

On April 10th, Apple and Google announced a joint initiative to deploy contact tracing functionality to the billions of devices running iOS or Android in the coming months. As part of this announcement, the companies shared draft specifications for the cryptography, hardware, and software involved in their proposed solution.

In this article,

we’ll take a first look at these specifications —

particularly Apple’s proposed Exposure framework —

and use what we’ve learned to anticipate what

this will all look like in practice.

What is contact tracing?

Contact tracing is a technique used by public health officials to identify people who are exposed to an infectious disease in order to slow the spread of that illness within a population.

When a patient is admitted to a hospital and diagnosed with a new, communicable disease, they’re interviewed by health workers to learn who they’ve interacted recently. Any contacts whose interactions with the patient are then evaluated, and if they’re diagnosed with the disease, the process repeats with their known, recent contacts.

Contact tracing disrupts the chain of transmission. It gives people the opportunity to isolate themselves before infecting others and to seek treatment before they present symptoms. It also allows decision-makers to make more informed recommendations and policy decisions about additional measures to take.

If you start early and act quickly, contact tracing gives you a fighting chance of containing an outbreak before it gets out of hand.

Unfortunately, we weren’t so lucky this time around.

With over a million confirmed cases of COVID-19 worldwide, many regions are well past the point where contact tracing is practical. But that’s not to say that it can’t play an essential role in the coming weeks and months.

“Only Apple (and Google) can do this.”

Since the outbreak, various governments and academics have proposed standards for contact tracing. But the most significant development so far came yesterday with Apple and Google’s announcement of a joint initiative.

According to the NHS, around 60% of adults in a population would need to participate in order for digital contact tracing to be effective. Researchers from the aforementioned institutions have noted that the limits imposed by iOS on 3rd-party apps make this level of participation unlikely.

On the one hand, it feels weird to congratulate Apple for stepping in to solve a problem it created in the first place. But we can all agree that this announcement is something to celebrate. It’s no exaggeration to say that this wouldn’t be possible without their help.

What are Apple and Google proposing as a solution?

At a high level, Apple and Google are proposing a common standard for how personal electronic devices (phones, tablets, watches) can automate the process of contact tracing.

Instead of health workers chasing down contacts on the phone — a process that can take hours, or even days — the proposed system could identify every recent contact and notify all of them within moments of a confirmed, positive diagnosis.

Apple’s CEO, Tim Cook, promises that “Contact tracing can help slow the spread of COVID-19 and can be done without compromising user privacy.”. The specifications accompanying the announcement show how that’s possible.

Let’s take them in turn, starting with cryptography (key derivation & rotation), followed by hardware (Bluetooth), and software (app) components.

Cryptography

When you install an app and open it for the first time, the Exposure Notification framework displays a dialog requesting permission to enable contact tracing on the device.

If the user accepts, the framework generates a 32-byte cryptographic random number to serve as the device’s Tracing Key. The Tracing Key is kept secret, never leaving the device.

Every 24 hours,

the device takes the Tracing Key and the day number (0, 1, 2, …)

and uses

HKDF

to derive a 16-byte Daily Tracing KeyTemporary Exposure Key.

These keys stay on the device,

unless you consent to share them.

Every 15 minutes, the device takes the Temporary Exposure Key and the number of 10-minute intervals since the beginning of the day (0 – 143), and uses HMAC to generate a new 16-byte Rolling Proximity Identifier. This identifier is broadcast from the device using Bluetooth LE.

If someone using a contact tracing app gets a positive diagnosis, the central health authority requests their Temporary Exposure Keys for the period of time that they were contagious. If the patient consents, those keys are then added to the health authority’s database as Positive Diagnosis Keys. Those keys are shared with other devices to determine if they’ve had any contact over that time period.

Hardware

Bluetooth organizes communications between devices around the concept of services.

A service describes a set of characteristics for accomplishing a particular task. A device may communicate with multiple services in the course of its operation. Many service definitions are standardized so that devices that do the same kinds of things communicate in the same way.

For example, a wireless heart rate monitor that uses Bluetooth to communicate to your phone would have a profile containing two services: a primary Heart Rate service and a secondary Battery service.

Apple and Google’s Contact Tracing standard defines a new Contact Detection service.

When a contact tracing app is running (either in the foreground or background), it acts as a peripheral, advertising its support for the Contact Detection service to any other device within range. The Rolling Proximity Identifier generated every 15 minutes is sent in the advertising packet along with the 16-bit service UUID.

Here’s some code for doing this from an iOS device using the Core Bluetooth framework:

import CoreAt the same time that the device broadcasts as a peripheral, it’s also scanning for other devices’ Rolling Proximity Identifiers. Again, here’s how you might do that on iOS using Core Bluetooth:

let delegate: CBCentralBluetooth is an almost ideal technology for contact tracing. It’s on every consumer smart phone. It operates with low power requirement, which lets it run continuously without draining your battery. And it just so happens to have a transmission range that approximates the physical proximity required for the airborne transmission of infectious disease. This last quality is what allows contact tracing to be done without resorting to location data.

Software

Your device stores any Rolling Proximity Identifiers it discovers, and periodically checks them against a list of Positive Diagnosis Keys sent from the central health authority.

Each Positive Diagnosis Key corresponds to someone else’s Temporary Exposure Key. We can derive all of the possible Rolling Proximity Identifiers that it could advertise over the course of that day (using the same HMAC algorithm that we used to derive our own Rolling Proximity Identifiers). If any matches were found among your device’s list of Rolling Proximity Identifiers, it means that you may have been in contact with an infected individual.

Suffice to say that digital contact tracing is really hard to get right. Given the importance of getting it right, both in terms of yielding accurate results and preserving privacy, Apple and Google are providing SDKs for app developers to use for iOS and Android, respectively.

All of the details we discussed about cryptography and Bluetooth are managed by the framework. The only thing we need to do as developers is communicate with the user — specifically, requesting their permission to start contact tracing and notifying them about a positive diagnosis.

ExposureNotification

When Apple announced the Contact framework on April 10th,

all we had to go on were some annotated Objective-C headers.

But as of the first public beta of iOS 13.5,

we now have official documentation

under its name: Exposure.

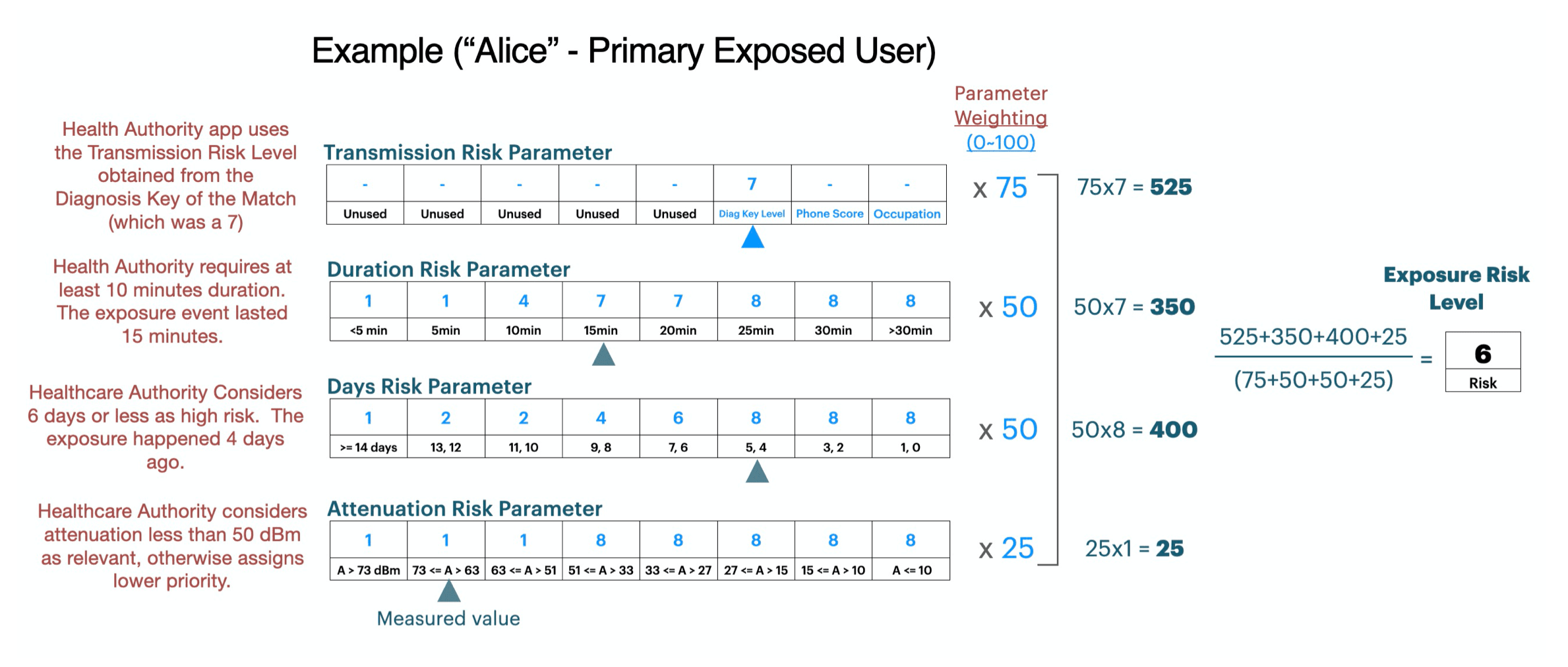

Calculating Risk of Exposure

A contact tracing app regularly fetches new Positive Diagnosis Keys from the central health authority. It then checks those keys against the device’s Rolling Proximity Identifiers. Any matches would indicate a possible risk of exposure.

In the first version of Contact,

all you could learn about a positive match was

how long you were exposed (in 5 minute increments)

and when contact occurred (with an unspecified level of precision).

While we might applaud the level of privacy protections here,

that doesn’t offer much in the way of actionable information.

Depending on the individual,

a push notification saying

“You were in exposed for 5–10 minutes sometime 3 days ago”

could warrant a visit to the hospital

or elicit no more concern than a missed call.

With Exposure,

you get a lot more information, including:

- Days since last exposure incident

- Cumulative duration of the exposure (capped at 30 minutes)

- Minimum Bluetooth signal strength attenuation (Transmission Power - RSSI), which can tell you how close they got

- Transmission risk, which is an app-definied value that may be based on symptoms, level of diagnosis verification, or other determination from the app or a health authority

For each instance of exposure,

an ENExposure

object provides all of the aforementioned information

plus an overall risk score

(from 1 to 8),

which is calculated from

the app’s assigned weights for each factor,

according to this equation:

S is a score, W is a weighting, r is risk, d is days since exposure, t is duration of exposure, ɑ is Bluetooth signal strength attenuation</em>

Apple provides this example in their framework documentation PDF:

Managing Permissions and Disclosures

The biggest challenge we found with the original Contact Tracing framework API was dealing with all of its completion handlers. Most of the functionality was provided through asynchronous APIs; without a way to compose these operations, you can easily find yourself nested 4 or 5 closures deep, indented to the far side of your editor.

Fortunately,

the latest release of Exposure Notification includes a new

ENManager class,

which simplifies much of that asynchronous state management.

let manager = ENManager()

manager.activate { error in

guard error == nil else { … }

manager.setTracing a path back to normal life

Many of us have been sheltering in place for weeks, if not months. Until a vaccine is developed and made widely available, this is the most effective strategy we have for stopping the spread of the disease.

But experts are saying that a vaccine could be anywhere from 9 to 18 months away. “What will we do until then?”

At least here in the United States, we don’t yet have a national plan for getting back to normal, so it’s hard to say. What we do know is that it’s not going to be easy, and it’s not going to come all at once.

Once the rate of new infections stabilizes, our focus will become containing new outbreaks in communities. And to that end, technology-backed contact tracing can play a crucial role.

From a technical perspective, Apple and Google’s proposal gives us every reason to believe that we can do contact tracing without compromising privacy. However, the amount of faith you put into this solution depends on how much you trust these companies and our governments in the first place.

Personally, I remain cautiously optimistic. Apple’s commitment to privacy has long been one of its greatest assets, and it’s now more important than ever.