Core Location in iOS 8

For as long as the iPhone has existed, location services have been front and center. Maps.app was one of the killer features that launched with the original iPhone. The Core Location API has existed in public form since the first public iPhone OS SDK. With each release of iOS, Apple has steadily added new features to the framework, like background location services, geocoding, and iBeacons.

iOS 8 continues that inexorable march of progress. Like many other aspects of the latest update, Core Location has been shaken up, with changes designed both to enable developers to build new kinds of things they couldn’t before and to help maintain user privacy. Specifically, iOS 8 brings three major sets of changes to the Core Location framework: more granular permissions, indoor positioning, and visit monitoring.

Permissions

There are a number of different reasons an app might request permission to access your location. A GPS app that provides turn-by-turn directions needs constant access to your location so it can tell you when to turn. A restaurant recommendation app might want to be able to access your location (even when it’s not open) so it can send you a push notification when you’re near a restaurant your friends like. A Twitter app might want your location when it posts, but shouldn’t need to monitor your location when you’re not using it.

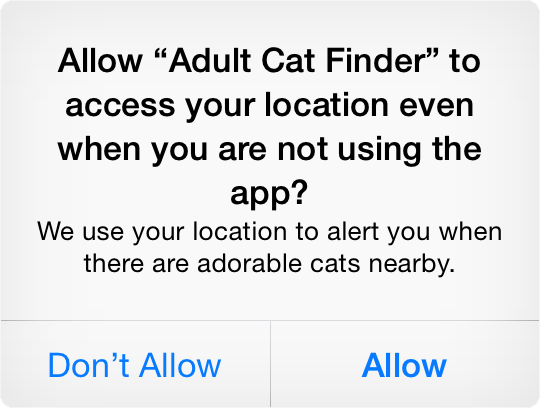

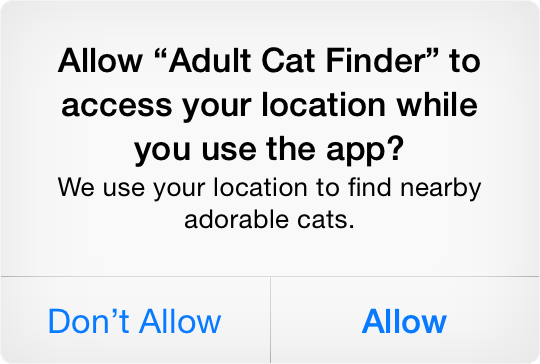

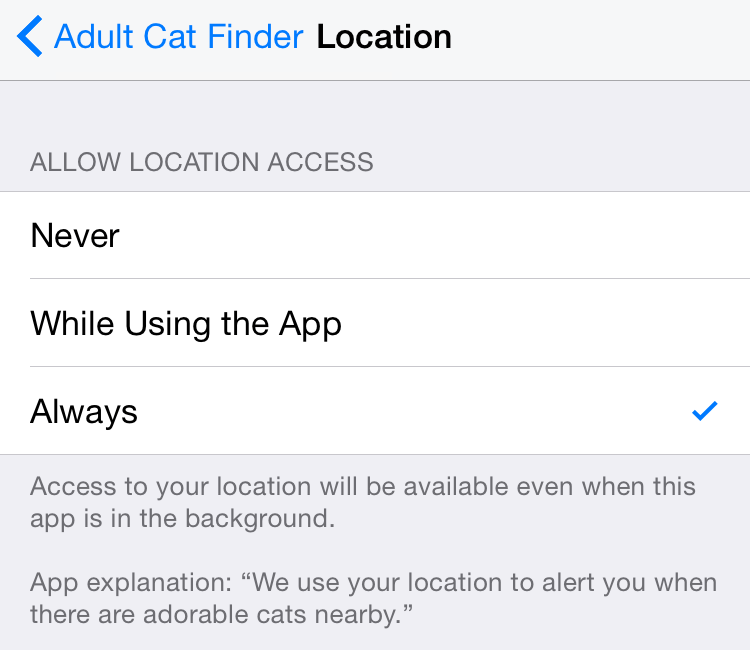

Prior to iOS 8, location services permissions were binary: you either gave an app permission to use location services, or you didn’t. Settings.app would show you which apps were accessing your location in the background, but you couldn’t do anything about it short of blocking the app from using location services entirely.

iOS 8 fixes that by breaking up location services permissions into two different types of authorization.

-

“When In Use” authorization only gives the app permission to receive your location when — you guessed it — the app is in use.

-

“Always” authorization, gives the app traditional background permissions, just as has always existed in prior iOS versions.

This is a major boon for user privacy, but it does mean a bit more effort on the part of us developers.

Requesting Permission

In earlier versions of iOS, requesting permission to use location services was implicit. Given an instance of CLLocation, the following code would trigger the system prompting the user to authorize access to location services if they hadn’t yet explicitly approved or denied the app:

import Foundation

import CoreTo make things simpler, assume we’ve declared a

managerinstance as a property for all the examples to come, and that its delegate is set to its owner.

The very act of telling a CLLocation to get the latest location would cause it to prompt for location services permission if appropriate.

With iOS 8, requesting permission and beginning to use location services are now separate actions. Specifically, there are two different methods you can use to explicitly request permissions: request and request. The former only gives you permission to access location data while the app is open; the latter gives you the traditional background location services that prior versions of iOS have had.

if CLLocationor

if CLLocationSince this happens asynchronously, the app can’t start using location services immediately. Instead, one must implement the location delegate method, which fires any time the authorization status changes based on user input.

If the user has previously given permission to use location services, this delegate method will also be called after the location manager is initialized and has its delegate set with the appropriate authorization status. Which conveniently makes for a single code path for using location services.

func locationDescriptive String

Another change is required to use location services in iOS 8. In the past, one could optionally include a ‘NSLocationUsageDescription’ key in Info.plist. This value was a plain-text string explaining to the user for what the app was planning to use location services. This has since been split up into two separate keys (NSLocation and NSLocation), and is now mandatory; if you call request or request without the corresponding key, the prompt simply won’t be shown to the user.

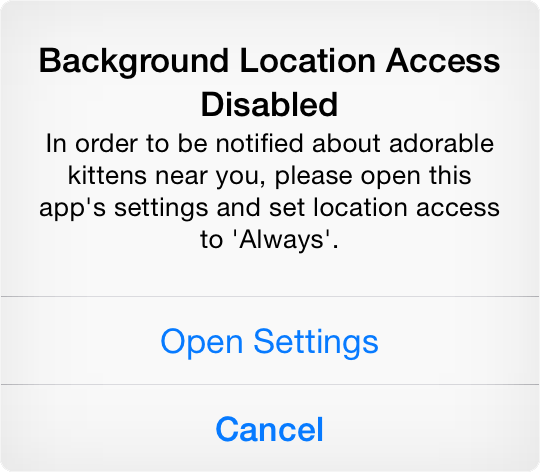

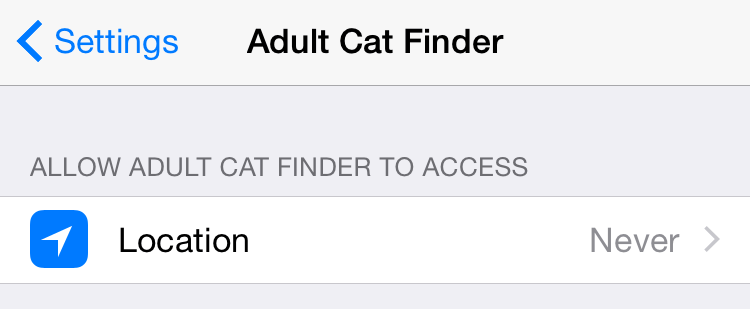

Requesting Multiple Permissions

Another detail worth noting is that the authorization pop-up will only ever be shown to a user once. After CLLocation returns anything other than Not, calling either request or request won’t result in a UIAlert being displayed to the user. After the user’s initial choice, the only way to change authorization settings is to go to Settings.app and go to either the privacy settings or the settings page for that specific app.

While more of an inconvenience under the old permission system, this significantly complicates things if an app asks for both “when-in-use” and “always” authorization at different times in its lifecycle. To help mitigate this, Apple has introduced a string constant, UIApplication, that represents a URL that will open the current app’s settings screen in Settings.app.

Here’s an example of how an app that prompts for both kinds of permissions might decide what to do when trying to prompt for Always permissions.

switch CLLocation

Backwards Compatibility

All of these new APIs require iOS 8. For apps still supporting iOS 7 or earlier, one must maintain two parallel code paths—one that explicitly asks for permission for iOS 8 and one that maintains the traditional method of just asking for location updates. A simple implementation might look something like this:

func triggerBuilding User Trust

There is a common thread running throughout all of the changes in iOS 8: they all make it easier to earn the trust of your users.

Explicit calls to request authorization encourage apps to not ask for permission until the user attempts to do something that requires authorization. Including a usage description makes it easy to explain why you need location access and what the app will use it for. The distinction between “When In Use” and “Always” authorization makes users feel comfortable that you only have as much of their data as is needed.

Of course, there is little in these new APIs to stop one from doing things the same way as always. All one “needs” to do for iOS 8 support is to add in a call to use and add in a generic usage string. But with these new changes, Apple is sending the strong message that you should respect your users. Once users get accustomed to apps that respect users’ privacy in this way, it isn’t hard to imagine that irresponsible use of location services could result in negative App Store ratings.

Indoor Positional Tracking

If one were to peruse the API diffs for Core, among the most baffling discoveries would be the introduction of CLFloor, a new object with a quite simple interface:

class CLFloor : NSObject {

var level: Int { get }

}

@interface CLFLoor : NSObject

@property(readonly, nonatomic) NSInteger level

@end

That’s it. A single property, an integer that tells you what floor of a building the location represents.

Europeans will surely be glad to know that the ground floor of a building is represented by ‘0’, not ‘1’.

A CLLocation object returned by a CLLocation may include a floor property, but if you were to write a sample app that used location services you’d notice that your CLLocation objects’ floor property was always nil.

That’s because this API change is the tip of the iceberg for a larger suite of features introduced in iOS 8 to facilitate indoor location tracking. For developers building applications in large spaces, like art museums or department stores, Apple now has tooling to support IPS using the built-in Core Location APIs and a combination of WiFi, GPS, cellular, and iBeacon data.

That said, information about this new functionality is surprisingly hard to come by. The program is currently limited to businesses who have applied for the program via Apple Maps Connect, with a pretty strict barrier to entry. Limited information about the program was outlined in this year’s WWDC (Session 708: Taking Core Location Indoors), but for the most part, most logistical details are locked behind closed doors. For all but the most well-connected of us, we have no choice but to be content writing this off as an idle curiosity.

CLVisit

In many apps, the reason to use location monitoring is determining whether a user is in a given place. Conceptually, you’re thinking in terms of nouns like “places” or “visits”, rather than raw GPS coordinates.

However, unless you have the benefit of being able to use region monitoring (which is limited to a relatively small number of regions) or iBeacon ranging (which requires beacon hardware to be physically installed in a space) Core Location’s background monitoring tools aren’t a great fit. Building a check-in app or a more comprehensive journaling app along the lines of Moves has traditionally meant eating up a lot of battery life with location monitoring and spending a lot of time doing custom processing.

With iOS 8, Apple has tried to solve this by introducing CLVisit, a new type of background location monitoring. A single CLVisit represents a period of time a user has spent in a single location, including both a coordinate and start / end timestamps.

In theory, using visit monitoring is no more work than any other background location tracking. Simply calling manager.start will enable background visit tracking, assuming the user has given Always authorization to your app. Once started, your app will be woken up periodically in the background when new updates come in. Unlike with basic location monitoring, if the system has a number of visit updates queued up (typically by enabling deferred updates), your delegate method will be called multiple times, with each call having a single visit, rather than the array of CLLocation objects that location is called with. Calling manager.stop will stop tracking.

Handling Visits

Each CLVisit object contains a few basic properties: its average coordinate, a horizontal accuracy, and dates for arrival and departure times.

Every time a visit is tracked, the CLLocation might be informed twice: once while the user has just arrived to a new place, and again when they leave it. You can figure out which is which by checking the departure property; a departure time of NSDate.distant means that the user is still there.

func locationCaveat Implementor

CLVisit is, as of iOS 8.1, not all that precise. While start and end times are generally accurate within a minute or two, lines get blurred at the edges of what is and what is not a visit. Ducking into a corner coffee shop for a minute might not trigger a visit, but waiting at a particularly long traffic light might. It’s likely that Apple will improve the quality of visit detection in future OS upgrades, but for now you might want to hold off on relying on CLVisit in favor of your own visit detection for use cases where it’s vital your data is as accurate as it can be.