NSURL /NSURLComponents

There is a simple beauty to—let’s call them “one-dimensional data types”: numbers or strings formatted to contain multiple values, retrievable through a mathematical operator or parsing routine. Like how the hexadecimal color #EE8262</code> can have red, green, and blue components extracted by masking and shifting its bits, or how regular expressions can match and capture complex patterns in just a few characters.

Of all the one-dimensional data types out there, URIs reign supreme. Here, in a single, human-parsable string, is every conceivable piece of information necessary to encode the location of any piece of information that has, does, and will ever exist on a computer.

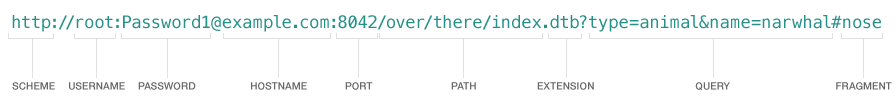

In its most basic form, a URI is comprised of a scheme name and a hierarchical part, with an optional query and fragment:

<scheme name> : <hierarchical part> [ ? <query> ] [ # <fragment> ]

Many protocols, including HTTP, specify a regular structure for information like the username, password, port, and path in the hierarchical part:

A solid grasp of network programming is rooted in an unshakeable familiarity with URL components. As a software developer, this means having a command over the URI functionality in your programming language’s standard library.

If a programming language does not have a URI module in its standard library, run, don’t walk, to a real language that does.

In Foundation, URLs are represented by NSURL.

NSURL instances are created using the NSURL(string:) initializer:

let url = NSURL(string: "http://example.com/")

NSURL *url = [NSURL URLWithIf the passed string is not a valid URL, this initializer will return nil.

NSString also has some vestigial functionality for path manipulation, as described a few weeks back, but that’s being slowly migrated over to NSURL. While the extra conversion from NSString to NSURL is not the most convenient step, it’s always worthwhile. If a value is a URL, it should be stored and passed as an NSURL; conflating the two types is reckless and lazy API design.

NSURL also has the initializer NSURL(string:relative, which can be used to construct a URL from a string relative to a base URL. The behavior of this method can be a source of confusion, because of how it treats leading /’s in relative paths.

For reference, here are representative examples of how this method works:

let baseNSURL *baseURL Components

NSURL provides accessor methods for each of the URL components as defined by RFC 2396:

absoluteString absoluteURL baseURL fileSystem Representation fragmenthostlastPath Component parameterString passwordpathpathComponents pathExtension portqueryrelativePath relativeString resourceSpecifier schemestandardizedURL user

The documentation and examples found in NSURL’s documentation are a great way to familiarize yourself with all of the different components.

Although username & password can be stored in a URL, consider using

NSURLCredentialwhen representing user credentials, or persisting them to the keychain.

NSURLComponents

Quietly added in iOS 7 and OS X Mavericks was NSURLComponents, which can best be described by what it could have been named instead: NSMutable.

NSURLComponents instances are constructed much in the same way as NSURL, with a provided NSString and optional base URL to resolve against (NSURLComponents(string:) & NSURLComponents(URL:resolving). It can also be initialized without any arguments to create an empty storage container, similar to NSDate.

The difference here, between NSURL and NSURLComponents, is that component properties are read-write. This provides a safe and direct way to modify individual components of a URL:

schemeuserpasswordhostportpathqueryfragment

Attempting to set an invalid scheme string or negative port number will throw an exception.

In addition, NSURLComponents also has read-write properties for percent-encoded versions of each component.

percentEncoded User percentEncoded Password percentEncoded Host percentEncoded Path percentEncoded Query percentEncoded Fragment

Getting these properties retains any percent encoding these components may have. Setting these properties assumes the component string is already correctly percent encoded. Attempting to set an incorrectly percent encoded string will cause an exception. Although ‘;’ is a legal path character, it is recommended that it be percent-encoded for best compatibility with NSURL (

String’sstringwill percent-encode any ‘;’ characters if you pass theBy Adding Percent Encoding With Allowed Characters(_:) URLPath).Allowed Character Set

More recently, NSURLComponents gained a query array, giving easy access to any key-value pairs encoded in a URL’s query string as an array of NSURLQuery.

Percent-Encoding

Speaking of percent-encoding…

OS X 10.9 and iOS 7 brought new String/NSString APIs for handling percent-encoding that improve upon (and deprecate) the old encoding-based NSString methods and the CFURL-related C APIs. To percent-encode a string, use the string with the relevant NSCharacter:

let title = "NSURL / NSURLComponents"

if let escapedNSString *title = @"NSURL / NSURLComponents";

NSString *escapedReversing the encoding is even easier, accomplished on an encoded string with string. New character sets have been added for each of the six URL components that might require percent-encoding:

// Predefined character sets for the six URL components and subcomponents which allow percent encoding. These character sets are passed to -string// Predefined character sets for the six URL components and subcomponents which allow percent encoding. These character sets are passed to -stringByAddingPercentEncodingWithAllowedCharacters:.

@interface NSCharacterSet (NSURLUtilities)

+ (NSCharacterSet *)URLUserAllowedCharacterSet;

+ (NSCharacterSet *)URLPasswordAllowedCharacterSet;

+ (NSCharacterSet *)URLHostAllowedCharacterSet;

+ (NSCharacterSet *)URLPathAllowedCharacterSet;

+ (NSCharacterSet *)URLQueryAllowedCharacterSet;

+ (NSCharacterSet *)URLFragmentAllowedCharacterSet;

@end

Bookmark URLs

One final topic worth mentioning are bookmark URLs, which can be used to safely reference files between application launches. Think of them as a persistent file descriptor.

A bookmark is an opaque data structure, enclosed in an

NSDataobject, that describes the location of a file. Whereas path- and file reference URLs are potentially fragile between launches of your app, a bookmark can usually be used to re-create a URL to a file even in cases where the file was moved or renamed.

You can read more about bookmark URLs in “Locating Files Using Bookmarks” from Apple’s File System Programming Guide

Forget jet packs and flying cars—my idea of an exciting future is one where everything has a URL, is encoded in Markdown, and stored in Git. If your mind isn’t blown by the implications of a universal resource locator, then I would invite you to reconsider.

Like hypertext, universal identification is a philosophical concept that both pre-dates and transcends computers. Together, they form the fabric of our information age: a framework for encoding our collective understanding of the universe as a network of individual facts, in a fashion that is hauntingly similar to how the neurons in our brains do much the same.

We are just now crossing the precipice of a Cambrian Explosion in physical computing. In an internet of things, where every object of our lives has a URL and embeds an electronic soul, a digital consciousness will emerge. Not to say, necessarily, that the singularity is near, but we’re on the verge of something incredible.

Quite lofty implications for a technology used most often to exchange pictures of cats.